Barriers to ending amputee disability

- 11.07.2018

- EmmaArnold

- None

It is widely agreed by medical professionals, amputees and biomedical engineers alike, that adopting hi-tech prosthesis can help to improve the quality of life for amputees and those born without limbs, making them much less restricted by their disability.

But despite the rapid advancements being made to prosthetic technology, amputees face a multitude of challenges to secure and effectively operate hi-tech prosthesis.

Balancing funding

A lack of financial support is one of the biggest barriers blocking the large-scale adoption of hi-tech prosthesis, due to the significant cost associated with designing, testing and producing state-of-the-art limbs.

A basic prosthetic limb can cost as little as £50, with leading hi-tech prosthesis costing more than £80,000. In the UK, prosthetic limbs available through the NHS cost on average £2,500. Although better technology is available, given the current budget constraints, there is a question of ethics posed in order to balance the cost of hi-tech prosthesis with the number of people who will benefit.

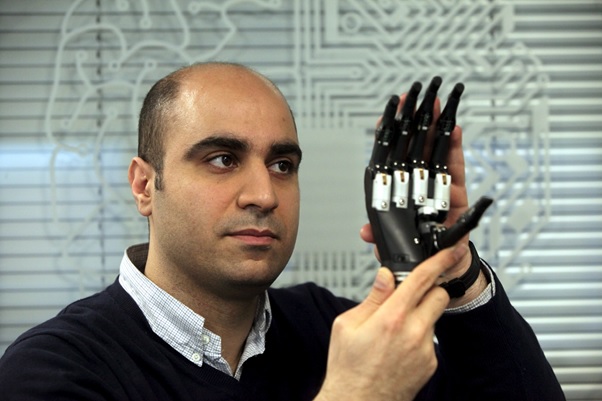

Dr Kianoush Nazarpour, reader in biomedical engineering at Newcastle University (pictured)

Dr Kianoush Nazarpour, says:

Fortunately or unfortunately, the number of amputees that there are does not justify the wide-scale use of high-end devices. In the UK, the NHS have to ask the question - do we want to spend £100,000 on one patient or 100 patients?

Double amputee and filmmaker, James Young, has a different view on the matter. He says: “A larger outlay on providing appropriate, functionally-advanced arms could reduce the financial burden on the NHS and government over the latter decades of an amputee’s life - but due to annual budgets and four-year elections, it’s hard for anyone in political or administrative positions to try and spend more in the short term to improve the total expenditure.”

Physical and psychological barriers

Coming to terms with losing a limb can be a problem in itself, without considering the physical and psychological challenges involved with learning how to operate a hi-tech prosthetic limb in order to live as independently as a person did before their amputation.

Regardless of the impressive advancements that have been made, for most people, state-of-the-art prosthetic devices are neither attainable, nor well suited to day-to-day life. For example, some myoelectric devices are not waterproof or durable enough to withstand daily use. This is a global issue, as documented by PBS that cite an American farmer who researchers gave a $100,000 myoelectric arm, but he kept it in a cupboard because he could not carry out his work using it.

James Young (pictured)

James Young adds: “Often prosthetics are prescribed and then never used by the patient when they go home. It’s not explained how things work or what they will do for you and there’s a lack of knowledge being shared. There are further issues in identifying need - finding the people that will definitely adopt the technology and help themselves with it.

“Psychologically, there’s a cognitive barrier, because we are animals and it’s difficult for many people - especially if they are accustomed to their disability - to change their habits and adopt something that’s completely alien to us, which operates on different mechanisms and principles to our own body.”

Issues with regulation

There is an ongoing ‘chicken and egg’ issue with new technologies becoming regulated that has created a barrier in new, more advanced limbs being made available. Speaking about the work his department carries out at Newcastle University, Dr Nazarpour, says: “If I have a device that I need to test, I cannot do so because it isn’t clinically approved. In order to gain approval, I need to run a range of clinical tests but I can’t because I don’t have the necessary permission - so it’s a self-perpetuating problem.”

James added:

What’s incredibly sad about the position amputees are in, is that the quality of life of many people is patched up with the minimum amount of technology. People are not going out because of socket pain, losing friends from being difficult to get around and are unable to be as productive in work all because the medical technology available through the NHS has left us behind.

"The microprocessor-controlled knee (that enables people to be more active, stops them from falling over, helps them recover from stumbles and allows them to walk more naturally) was released in 1997 - but only recently was it allowed funding through the NHS."

Scientific development

Despite the advancements that have been made within the prosthetics industry, around 20% of new limbs are still rejected by users according to the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Conventional amputations see doctors sever muscles, which usually help people control their limbs - leading many patients to reject replacement limbs.

Although extensive experiments have been carried out, scientists and prosthetists do not fully understand the complexity of the brain and what capacity it has to learn how to operate an unnatural limb. There are lots of questions that need to be answered before developments can progress further.

From a different perspective, James believes that the pace of scientific development is a significant barrier. He says: “Issues around prosthetic adoption can be mirrored in the commercial technology industry, like with mobile phones. For example, if I wanted to buy a new hand - do I get the iPhone X hand or the Google Pixel hand? Do I really want to spend an inordinate amount of money on a bionic limb, which I’ll have to live with for the next 50 years? What if there is another coming out next year that hasn’t been announced? What if five years from now there’s a new control system that comes out but my hand isn’t compatible with it?”

Breaking barriers

There is no doubt that prosthetic technology has significantly advanced - and it cannot be ignored that hi-tech prosthesis offer users significant benefits - however, there are significant barriers that prevent us from ending amputee disability with the technologies available today.

It will require in-depth research, innovative thinking and cooperation from a wide range of parties to make hi-tech prosthesis more accessible and effective so that we can move closer to ending amputee disability.

Next in the series

We recently ran a survey to gauge your thoughts on amputee disability, and next week we will be sharing our findings with you.

Remember to keep an eye on the blog and our social media channels to find out more about amputee disability and prosthetics over coming weeks.